Wednesday, February 29, 2012

Wednesday, February 15, 2012

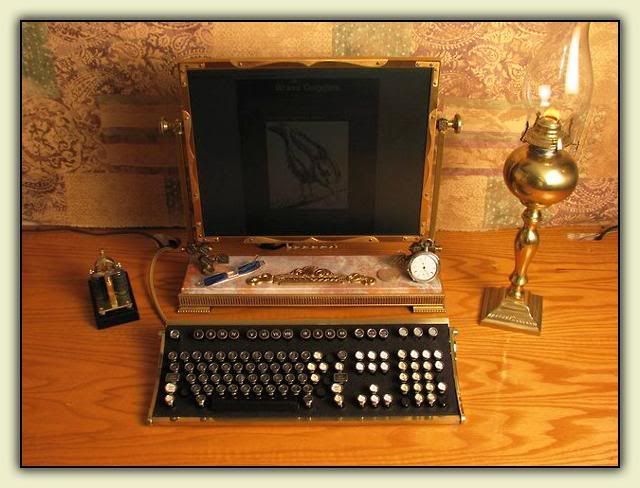

Steampunk music

Every movement needs its soundtrack, and steampunk is no exception. Although there is some debate as to what counts as steampunk music, if you plug a band into a list somewhere (Amazon, Spotify, Pandora) you will come up with groups that fit roughly into the category.

So, drop the name Abney Park into your favorite listening engine, and let the cog that is algorithm take you away on an airship ride of musicality.

This is probably my favorite explicitly steampunk band. Almost all of these bands are a little more earnest and melodramatic for my tastes, but if I'm in the mood for stuff that sounds like a soundtrack to a recent Sherlock Holmes movies, this is the ticket.

However, the entire concept of steampunk as a musical genre is open for interpretation, and one of my favorite interpretations of steampunk is that it evokes "an era that never was," alternative futures not premised out of our present and extrapolated into the far future, but rather alternative futures that are equivalent to our present but proceed as if history had developed differently.

Making use of this definition, I would list at least the following as relatively well-know steampunk bands:

Robyn Hitchcock--Imagine a trajectory where not everyone follows in the musical footsteps of The Beatles. This is not just the road not taken--it's more like platform 9 3/4. You can't get there from here.

Steely Dan--Imagine an alternative reality where when band members get together, a mysterious third being, a daemon, emerges and plays the most wonderful and scary stuff you've heard in your life.

The Traveling Wilburies--Imagine if four superstars got together and just hung out in someone's cabin in the Ozarks and sang songs together, folky and free. And they weren't superstars.

See the trend?

I think this is what at least some bands I know that are explicitly Christian have also tried to do, "steampunk" religious rock so it doesn't follow down the narrow and overbearing historical drift that is CCM.

The weirdest and best example of this is Half-Handed Cloud. This is a band that asks, "What if rock were played on toy instruments at twice the normal speed, one octave higher, and had pristine and theologically astute lyrics that were also ironic and playful?"

Another example here would be U2. What if a Christian rock band were the greatest rock band in the world and regularly dropped the F-bomb in interviews and conversation (this one might be a stretch).

Examples closer to home include my friends Jonathan Rundman and Nate Houge, who write liturgical rock (that is steampunk, my friends) and also think you can have a Christian vocational rock existence that includes writing plain old rock and roll.

Here's what we can learn from this, if nothing else. Sometimes it's worth doing something just because it is worth doing, because it is arty and weird and free. And sometimes the weirdest stuff strikes a chord, and people listen and stand in awe, and are invited to expand their imaginative horizons because they hear something, and they ask, "How do people even make music like that?"

And that, whenever if happens, is a boon to theological existence.

So, drop the name Abney Park into your favorite listening engine, and let the cog that is algorithm take you away on an airship ride of musicality.

This is probably my favorite explicitly steampunk band. Almost all of these bands are a little more earnest and melodramatic for my tastes, but if I'm in the mood for stuff that sounds like a soundtrack to a recent Sherlock Holmes movies, this is the ticket.

However, the entire concept of steampunk as a musical genre is open for interpretation, and one of my favorite interpretations of steampunk is that it evokes "an era that never was," alternative futures not premised out of our present and extrapolated into the far future, but rather alternative futures that are equivalent to our present but proceed as if history had developed differently.

Making use of this definition, I would list at least the following as relatively well-know steampunk bands:

Robyn Hitchcock--Imagine a trajectory where not everyone follows in the musical footsteps of The Beatles. This is not just the road not taken--it's more like platform 9 3/4. You can't get there from here.

Steely Dan--Imagine an alternative reality where when band members get together, a mysterious third being, a daemon, emerges and plays the most wonderful and scary stuff you've heard in your life.

The Traveling Wilburies--Imagine if four superstars got together and just hung out in someone's cabin in the Ozarks and sang songs together, folky and free. And they weren't superstars.

See the trend?

I think this is what at least some bands I know that are explicitly Christian have also tried to do, "steampunk" religious rock so it doesn't follow down the narrow and overbearing historical drift that is CCM.

The weirdest and best example of this is Half-Handed Cloud. This is a band that asks, "What if rock were played on toy instruments at twice the normal speed, one octave higher, and had pristine and theologically astute lyrics that were also ironic and playful?"

Another example here would be U2. What if a Christian rock band were the greatest rock band in the world and regularly dropped the F-bomb in interviews and conversation (this one might be a stretch).

Examples closer to home include my friends Jonathan Rundman and Nate Houge, who write liturgical rock (that is steampunk, my friends) and also think you can have a Christian vocational rock existence that includes writing plain old rock and roll.

Here's what we can learn from this, if nothing else. Sometimes it's worth doing something just because it is worth doing, because it is arty and weird and free. And sometimes the weirdest stuff strikes a chord, and people listen and stand in awe, and are invited to expand their imaginative horizons because they hear something, and they ask, "How do people even make music like that?"

And that, whenever if happens, is a boon to theological existence.

Permanent Guests: The Impossibility of Hospitality

Hospitality is all over the map. Everyone needs it or does it or wants to do it. There are lots of really good books on the subject in Christian thought. I've written on it with respect to religious pluralism at the Journal for Lutheran Ethics. The problem of inviting, having, and keeping a guest is so prevalent and part of our world it has its own tv trope, called "The Thing That Would Not Leave" for the Saturday Night Live sketch of the same name. One of my favorite movies, What About Bob? is in part about the host-guest and patron-client relationship. That's good chicken, no?

Hospitality is all over the map. Everyone needs it or does it or wants to do it. There are lots of really good books on the subject in Christian thought. I've written on it with respect to religious pluralism at the Journal for Lutheran Ethics. The problem of inviting, having, and keeping a guest is so prevalent and part of our world it has its own tv trope, called "The Thing That Would Not Leave" for the Saturday Night Live sketch of the same name. One of my favorite movies, What About Bob? is in part about the host-guest and patron-client relationship. That's good chicken, no?

As more writers have gotten into the hospitality business and as they've looked back at the history of human problems of managing and balancing hospitality, there's two basic problems that have emerged, embodied in the phrase "make yourself at home."

A person cannot make herself at home without making your home into hers. This estranges your home for the sake of the other. You cease to offer a welcome since you cede your own domicile. You become a stranger in your own home!

Or:

Welcoming the stranger into our home makes you part of us and you cease to be a guest or stranger. You cannot be a stranger (an other) and be part of our house.

Hence the humor and prevalence of the permanent guest as a horror story. And the proximity of this conflict of laws (antinomy) to how couples and families negotiate marriages and partnerships, blending homes and traditions and histories.

Anthropologists have noted that hospitality is about creating temporary spaces to tolerate this law of conflicts, about letting a guest in on what's going on at home in order to let the guest decide if she wants to join the domicile. But that upholds the antinomy, the conflict between these two laws.

Hospitality in this sense is radically intolerant because it either wants to reject the stranger (get that guest out of here, or at least into a room above the garage, like the Fonz) or to domesticate the stranger.

Christians have been laboring hard to overcome or mitigate the difficulties in this bind. It seems impossible to welcome a stranger without domesticating them. At the very least learning to identify how a community practices welcome and how it domesticates goes a long way toward resolving this problem.

These questions arise, for me: How many strangers can one host? Can one give up the domicile for the sake of the other? Christians should be able to welcome this problem. After all, they are a community where the faithless and hypocrites are welcomed and love is reserved for the enemy. None of these are good for communities, in an ordinary sense. But they are marks of the friends of Jesus and his welcome.

These questions arise, for me: How many strangers can one host? Can one give up the domicile for the sake of the other? Christians should be able to welcome this problem. After all, they are a community where the faithless and hypocrites are welcomed and love is reserved for the enemy. None of these are good for communities, in an ordinary sense. But they are marks of the friends of Jesus and his welcome.

Sources:

Emmanuel Levinas, Totality and Infinity

Julian Rivers, The Fate of Schechem or the Politics of Sex

Jacques Derrida, "A Word of Welcome" in Adieu to Levinas

Thursday, February 2, 2012

Not such a stretch

Worship and theology are steampunk by the very nature of the case. Much of Christian worship and theology drifts downstream from a different historical locus than the rest of culture. Both are an act of the imagination, living "as if" a different set of historical events had transpired than in the real history of the world.

Worship and theology are steampunk by the very nature of the case. Much of Christian worship and theology drifts downstream from a different historical locus than the rest of culture. Both are an act of the imagination, living "as if" a different set of historical events had transpired than in the real history of the world.So, for example, while the rest of the world wears clothes from the Gap, clergy in many worship places still wear cassocks and clericals developed during fashion moments now long lost in the steamy recesses of history.

Quite a lot of solid theology is also steampunk. Theologians love to imagine alternative historical developments. Two that immediately come to mind include Paul Hinlicky's Paths Not Taken (now there is a steampunk title!) and essentially the whole of Radical Orthodoxy, which seeks to use the tools of post-modernism to critique modernity and repristinate premodern philsophies and theologies.

All of this is, from my view, intrinsically interesting. Given the increasing cultural caché of steampunk as an art from and sub-culture, it leaves me wondering, is a blog on steampunk theology worth the time. I'm going to leave space for reader response to find out.

Will you read a blog on steampunk theology? Would you participate in the discussion? How are you living steampunk today?

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Introducing Steampunk Theology

Exploring the steampunk ethos as it relates to theology and worship. More goggles, brass, and leather than your typical church, but hey, most already have an organ.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)