[Read Part One. Part Two.]

[From the notebooks of Sub-Inspector Max H.]

We departed from Walter Benjamin’s library here in Paris, more unhappy than before. This seemed to cheer Weisengrund up.

Then it started to snow. We passed by a small church, the kind that you see rarely now days: peopled, all aglow with candlelight despite the ready availability of steam-electricity.

We heard them sing:

Magnificat anima mea Dominum,

et exsultavit spiritus meus in Deo salvatore meo,

quia respexit humilitatem ancillae suae.

Immediately Inspector T. A. Weisengrund stopped our journey toward the Paris offices of the Kulturindustrie.

He said: “Wait. We must listen.” This shocked me. “But Inspector, we can hardly care for this superstition. After all, listen to this song. “My Spirit”? “My soul”? “God”? These things are archaic survivalists, things yet to be liquidated by the modern, steam and materialist touch. We need to move on. I can hardly listen to this primitive music.”

“No, Sub-Inspector. This is one of the rare moments in this old stuff that touches on the truth of our matters. I hardly agree with the Magus of the North in his James Watt lecture, that steam is really Geist, but he is on to something here. The material, the steam, the physical is not just the kind of raw material that some propose. No atomists, we. Listen to this song. It shows the way forward. Yes, my soul, yes my spirit, yes, perhaps even to God because of the rest of this song.”

I was in shock. This is hardly the kind of morality I signed on for. Was the Inspector going in for some of this “return to theology” that was in the water? Did he read the leaflets of the Alpinist in the Americas about the undead?

“This song declares a god whose love of justice favors the lowly and casts down the mighty. There is no better song. It remembers the ancient man, the one long ago who left his homeland for the sake of a promise, perhaps the original materialist. You perhaps remember the phrase, Sub-Inspector? ‘My father is a wandering materialist’? This song is a fully materialist vision. It may be ideology in part. But every hope promises the basic tenant of a material hope: things could be different then they are.”

So we just listened.

Ecce enim ex hoc beatam me dicent omnes generationes,

quia fecit mihi magna,

qui potens est,

et sanctum nomen eius,

et misericordia eius in progenies et progenies

timentibus eum.

Fecit potentiam in brachio suo,

dispersit superbos mente cordis sui;

deposuit potentes de sede

et exaltavit humiles;

esurientes implevit bonis

et divites dimisit inanes.

Suscepit Israel puerum suum,

recordatus misericordiae,

sicut locutus est ad patres nostros,

Abraham et semini eius in saecula.

[Continue to Part Four.]

Sunday, December 23, 2012

Sunday, December 9, 2012

Nikolai

Looking through some collodion processed wet plates, I came across this image. Can anyone help me identify it? A small inscription at the bottom of the print reads "Nikolai"

Friday, December 7, 2012

"And the Dead Shall Rise?": Parts III and IV - Ghost Dances

Sometime near the End of A.D. 1899

To the Magus and the Ecclesiast,

The steam-powered cider mills along the shores of Lake

Ontario had ceased their churning, and the foliage, once transfigured by the created

fires of the autumn, had since cooled during the descent into ice and

winter. But the visitations of the (un?)-dead have not relented.

Neither had the sleepless nights spent listening to their ungodly

shuffling of feet beneath the panes of my parsonage (I no longer glimpsed their

ghastly visages peering through the leaded glass – I had blacked them out as

with sack cloth desperately hoping for repentance in the midst of this

Nineveh). It felt as if time

itself were slowly disintegrating, as if caught in the midst of a living Limbo

– and as their numbers swelled, I could not believe death had undone so many,

nor left so many so restless in their sleep, with an insomnia that now kept

awake the living.

The steam-powered cider mills along the shores of Lake

Ontario had ceased their churning, and the foliage, once transfigured by the created

fires of the autumn, had since cooled during the descent into ice and

winter. But the visitations of the (un?)-dead have not relented.

Neither had the sleepless nights spent listening to their ungodly

shuffling of feet beneath the panes of my parsonage (I no longer glimpsed their

ghastly visages peering through the leaded glass – I had blacked them out as

with sack cloth desperately hoping for repentance in the midst of this

Nineveh). It felt as if time

itself were slowly disintegrating, as if caught in the midst of a living Limbo

– and as their numbers swelled, I could not believe death had undone so many,

nor left so many so restless in their sleep, with an insomnia that now kept

awake the living.

Shortly after my encounter with Captain Priest, I returned

again to the public house (before, of course, the now routine hour at which the

former communicants of the parish gathered outside the doors of the church – we

had begun to establish such circumstances as predictable and regular), praying

an extra pint would provide the rest that extra prayers had promised and left undelivered.

I approached the man, and discovered that as he lifted his

eyes from beneath a wide-brimmed hat, that he was of indigenous heritage. I asked him of his tribe, and with

great sorrow in his once fiery eyes now black as spent ash, he told me he

belonged to the Paiute of the north.

I asked him his name. He

told me he had once been renowned as Wovoka, the “wood cutter.” But I could call him Jack. Jack Wilson.

I must confess, I nearly regurgitated my ale in the

venerable one’s face, for while my days had not hardly been short on wonders as

of late, I could scarce believe whose table I shared. Wovoka, I repeated.

Of the vision of the eclipse.

The one who was struck by the shell of a shotgun and yet lived. Wovoka, of the Ghost Dance?

I must confess, I nearly regurgitated my ale in the

venerable one’s face, for while my days had not hardly been short on wonders as

of late, I could scarce believe whose table I shared. Wovoka, I repeated.

Of the vision of the eclipse.

The one who was struck by the shell of a shotgun and yet lived. Wovoka, of the Ghost Dance?

I was once, he muttered, but please, Jack is all now. Wovoka controlled the weather. Wovoka levitated above the ground. Wovoka saw visions of the great Messiah

in the darkening of the sun. Jack

Wilson is what is left of him today, and I wander the land, sometimes searching

for Wovoka…but more often, searching for a way to escape the haunting of his

shadow.

We talked then for some time. Of his upbringing in the great western country, and of his

upbringing in the faith and devotion to Christ, apostles among the Lakota, and

of his vision in 1889, the vision of the rising of the dead and the restoration

of the land to its original inhabitants by the Messiah. And of course, of the Ghost Dance.

Surely, gentlemen, you have heard of this, even in the far

reaches of the world? The five-day

time of fasting, purification, of communion found dancing in the round that

sought to unite in mystic catholicity the diversity of native peoples and their

deities under the One great spirit, and so bring about a jubilee of justice and

shalom for those oppressed by the wrongs of our own ancestors? Surely, you have heard of Wounded Knee,

and the massacre of the Lakota there, for practicing the dance, in defiance of

the Bureau of Indian Affairs?

If I sound excited, it is because, as you have probably

already rightly guessed, I have been present at such a dance. Never dancing myself, not out of

conviction, but more so out of the embarrassment of my own Teutonic

heritage. To see the veil between time

and eternity, between the living and the dead, between the peoples we call

pagan and the people we call the communion of saints, so thinly stretched that

at any moment, righteousness and justice seemed ready to pour down like a

mighty stream of heavenly fire upon the earth…who could fail to be moved? Who could fail to forget?

The Alpinist, apparently. For, as marvelous a thing as it was to meet the Wovoka, now once more cloaking the

shame of his failed messianic expectations under the moniker of his youth,

himself a kind shade lost and wandering in the wasteland of our industrial

present, I was suddenly struck by the providence of our meeting. For the teaching of the Ghost Dance was

the anticipation of the Second Coming of the Messiah, and in it was enacted the

rising of the dead. The dancing,

the summoning of spirits…the literal intertwining of our Christian hope with

theirs. A purer reflection of the

current state of ghastliness now gripping my parish.

The Alpinist, apparently. For, as marvelous a thing as it was to meet the Wovoka, now once more cloaking the

shame of his failed messianic expectations under the moniker of his youth,

himself a kind shade lost and wandering in the wasteland of our industrial

present, I was suddenly struck by the providence of our meeting. For the teaching of the Ghost Dance was

the anticipation of the Second Coming of the Messiah, and in it was enacted the

rising of the dead. The dancing,

the summoning of spirits…the literal intertwining of our Christian hope with

theirs. A purer reflection of the

current state of ghastliness now gripping my parish.

My beverage remained in my mouth this time, despite my great

agitation, but as I reared up to share my revelation with the shaman, he was

gone. Vanished, as if he had never

existed except on the margins of sight, as something glimpsed on the corner of one’s

vision while rapidly passing on a steam train. I wonder to the day of this writing if I truly met Wovoka,

or if he was himself a kind of vision, the last echoes of the Ghost Dance

playing themselves out in an insomniac’s tenuous and failing grip with time and

space.

But, dear friends, Mr. Wilson’s legacy, his Ghost Dance,

plays like the score to this strange opera of horror, making possible narrative

and music where previously there was only speculation and ballyhoo. Is there perhaps something to the

presence of these walkers of the night, tied to our own Ghost Dance, the

rhythms of our liturgies, of the Eucharist – our bringing of a body long dead

and risen back into the cadences of the temporal? Has it been a narcissism of grave consequence to assume that

the dead are seeking us, seeking our harm?

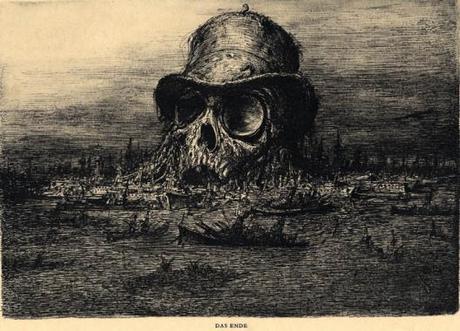

Perhaps the dead seek something else…perhaps they seek, not

our undoing, but their reconstitution.

Restless, like the native spirits, after a half-century of warfare,

death, unprecedented technological progress and unbearable social disintegration

and upheaval – horrors of our own making, come back to be horrors upon the

future? Perhaps it is not a sign of condemnation upon us, but the stirrings of

a longing for communion with us.

Might this explain their clustering at our doors?

I decided to test my hypothesis, and so called upon the

Christians of my parish – all sorts mind you, even the Romans – to gather the

next evening for an ecumenical mass.

The terrors of the night had become such that even members of the

Salvation Army, and some Latter Day Saints, darkened our doorways. I made sure all arrived while it was

still day, and made sure the liturgy would last through the setting of the sun.

Little did they know that I was conducting them through a kind of Ghost Dance

of our own, gathering the many into one, under the One who gathers all.

As I suspected, as darkness fell, the walkers arrived for

mass. The doors were locked and

bolted, and you can imagine the minor panic that arose among the frightened

worshippers when, while sharing the peace, the restless dead began clawing and

pushing at them. Steeling myself

against the pangs of my own terror, I called my deacons together and instructed

them, at the moment of the final communicant’s partaking, to throw open the

doors. I then gathered the people

together, arranged us in one great circle (I told you, it was our Ghost Dance

after all) and began the dialogue.

The banging and clatter continued their crescendo.

Have you ever said the words, “this is my body, broken for

you,” as broken, undead bodies clamor at your gates? Perhaps you have, for perhaps these are the circumstances at

every Eucharist, if we are honest with ourselves. I am in the habit of incorporating the words of St.

Augustine (who I would not have been surprised to see among that crowd of

deceased discontents) into my Eucharistic prayers, his own declaration,

uplifting the Host, to “behold what you are, become what you receive.” There were the bodies of the living,

and yet, the undead body of Christ, divided and rent. There were the bodies of the dead, restlessly alive, seeking

admission. There was the

church. There was the end.

Have you ever said the words, “this is my body, broken for

you,” as broken, undead bodies clamor at your gates? Perhaps you have, for perhaps these are the circumstances at

every Eucharist, if we are honest with ourselves. I am in the habit of incorporating the words of St.

Augustine (who I would not have been surprised to see among that crowd of

deceased discontents) into my Eucharistic prayers, his own declaration,

uplifting the Host, to “behold what you are, become what you receive.” There were the bodies of the living,

and yet, the undead body of Christ, divided and rent. There were the bodies of the dead, restlessly alive, seeking

admission. There was the

church. There was the end.

The doors were flung open at my appointed time. The people were already seated and

calmed, as if the familiarity of the liturgy and its timeless beauty had

soothed them into a welcome escape.

And so came my final communicants.

They thundered down the aisle, desperately loping towards me, and to

recall the grim details of their eyes (or lack thereof), their mangled corpses,

would make even the most stalwart leprosy doctor vomit and cringe. And yet, as the living fainted and

wailed, the dead came to the altar.

And the marvel, which I am sure you will deem a sign of my

insanity: as each grasped the host and brought it to whatever passed as lips –

they scattered. Into dust. As if the weight of the thing simply

caused them to collapse.

Like snowbanks perched tenuously on the edge of a rooftop, blown into

powder and dissipating in gaslight.

I swear upon my oath of office and my ordination vows. And within a half hour, the last of the

walkers walked no more. And the

Ghost Dance was ended.

Surely, brothers, it will take some time for you to read

this story, perhaps longer to convince yourselves I am not fabricating it or

that I have not lost my mind, and perhaps, even longer still, to come to grips

with its mystery. I myself have

scarcely begun to unravel it. Nor

do I think I should write to Captain Priest, for example, and suggest that the

remedy to all such hauntings is the shamanical admistration of the Eucharist –

she is not that kind of Priest, after all.

I am still amazed and puzzled, and perhaps ever shall be, by

the restless dead, called up into restlessness out of the desire for rest. Why it took Wovoka, and not Augustine

or Luther or some other shade of my own past, to re-incorporate my own zombied

memories and bring them back to the harmonious rhythms of the circle and the

time-keeping that is liturgy. Why

it is in this age that Irish pagans and Paiute and Lakota and airship captains

and adventurers freely glimpse beyond the veil of the finite, while the

enlightened among us wallow in terror our rationalities are helpless to

alleviate. Why it happened now,

and what it means for us all at the closing of the age this century has

wrought.

So for now, silence.

As the scraping of hands and the moaning of the dead gives way to the

softness of falling snow, so must these words cease, and must I at last, after

many weary nights, receive with gratitude the gift of a good night’s

sleep. Ponder with me, in the meantime

my friends, the meaning of these events.

And for God’s sake, if you haven’t recently, do your un-dead bodies a

favor, and get thee to a Eucharist.

Grace, peace and all my love,

The Alpinist

Thursday, November 29, 2012

Phenomenology of Geist

Friends: I have just returned to my bed and breakfast after a remarkable visit to a café-net. The owner of this café has discovered a remarkable use for Geist. Tables in this café have been arranged with approximately four to six phenom-graphs sitting around the table, or standing in the corner as a cluster. Participants can sit at any phenom-graph in any café, and transmit their voices to any phenom-graph elsewhere.

I sat down at a table alone, near a table with three active graphs. The proprietor kindly allowed me to experiment with a phenom-graph transcription device. I had the opportunity to overhear the following conversation, which I transcribed feverishly. Since I do not know the names of those speaking, I have given them monikers.

--

The Professor: I guess I do not see what is at stake in saying "this phenom-graph is not instrumental" -- when I see people using it as a tool all the time.

The cleric: For me what is at stake is that it doesn't HAVE to be instrumentalized, whereas almost all of the conversation around this assumes it is mostly or even exclusively an instrument. And when it is understood in new non-instrumentalist ways, it furthers mission. That's my stake.

The Professor: To be clear I posed the question: given the positive and mutual beneficient experience you have in mind -- is that experience using Geist media as an instrument or to open up a world/environment? Some have said it is a false dichotomy and waved their hands at habitus, ala Bourdieu. I do not know if this works.

The cleric: I've never linked habitus in my mind with Bourdieu, but then I've probably just not read enough of him. I see opportunities for social media to open up a world/environment. That's why I defend it against implicit or explicit instrumentalization.

The Professor: habitus is supposed to get us over the idea that there's a self and then there's the stuff the self does and that the self is always first. Habitus is to say that the self is in acting. It's in his essay on practice s, he basically said there's no difference than instrument and environment making. I think that skirts a ton of issues because it is basically an attempt to self-hood is fluid and is in practice, which still maintains the priority of the agent . Selfhood is never like that and it is not proper to theological anthropology , selfhood is always ecstatic -- I am who I am in Christ-Geist and in the neighbor-- I am given by another, promised even.

The Adjunct: The phenomenological evidence: When I returned from our conference this afternoon I was greeted by my son's play date he organized on phenom-media...all on their individual devices, proximate or expansive empathy/intimacy? It seems they're cultivating experiences in a shared environment.

The Professor: What is this giving them? that's the other way to think it. Or to put it in terms of hydrogen weapons. It is a tool. But a tool that could utterly change the world. The Eucharist may seem like a tool. But it changes the entire world and selves with it.

The Cleric: There's no difference between an instrumental and environmental use of tech. Mostly people simply aren't even aware of media effects, and this causes all kinds of confusion.

[here there is a mumbled conversation about graphic art I missed while my barrista came to the table offering another espresso]

The Cleric: Hmmmm... I still have no idea what phenomenology is, so I'm probably one without knowing it. And it's not for lack of trying. I've read some of the works by Earl van Huss. Here, take this for example [at which point he read from a book... but one problem with this medium is unless people verbally name their bibliographic reference, there is no way to know]:

The Cleric: To me, that's just life. I don't get how it is a philosophical orientation.

The Professor: You would be the first to claim that phenomenology is common sense. I think you're missing the epoche -- the bracketing out of other considerations. To open up the phenomenon.

The Adjunct: For what its worth, my colleague wrote briefly on this topic, asking the question: How does one render public and explicit a supposedly authoritative text in a culture of pluralism in such a way that it functions normatively for real persons? This I believe is a fundamentally phenomenological question.

The Cleric: Okay, you both are helping. This becomes SO frustrating for me. I don't get it. I've tried multiple times to understand how the phenomenology of Geist is a philosophical discipline, and I fail. My only theory right now is that I'm a "natural" phenomenologist and so I don't get the theory around it because it's how I function naturally all the time anyway. What I especially don't get is what you emphasize above, Professor, the "bracketing out of other considerations." What other considerations? This isn't clear to me at all. Here's a quote from the essay you reference, Adjunct, that is an example of why this whole thing remains opaque to me, I guess opaque precisely in its transparency:

The Professor: Here's probably why you are having trouble: 1) phenomenology and hermeneutics dovetail into each other with Gadamer -- you've probably drunk so deeply here that some of the habits of thought that constittue how you look at things or read texts is phenomenological. This includes: 1) the idea of horizons and its fusion 2) the language of the "other" and distanciation .

Theology of the cross does not say things are what they seem to be. Phenomenology asks us (in its Earl van Hussian mode) to bracket what something is according to our natural attitude, how things appear to our senses in order to allow us to consider the object in its full giveness. Things are, according to van Huss, what they are according to how they give themselves. For Heidegger, things disclose being -- this is why for Heidegger technology is so important becuase tech changes the way we are, our very being, our very world. Things are, according to Marion, their giveness. Phenomenology is not just to attend to our senses but to consider how things are while our natural attitude is left aside. This allows us to consider what truth is disclosed in fiction in the phenomenological sense.

Theology of the cross is a quasi-phenomenological exercise since it asks us to bracket out our desire to write God large and see how suffering discloses God. you are not considering the problems that Kant introduced to which phenomenology is in large part the answer. Kant's distinction between phenomena and noumena. Our knowing can never get to what things are in themselves, according to Kant, to drastically simplify.

Being Given by Marion is your ticket. Or Husserl's Cartesian Meditations. I don't know any other way here. Read it and tell me what doesn't work. If you don't get the Kant problems on knowing and how one can't have an experience of God in his critique of what he calls the transcendental ideas (God, human self/soul, and human freedom) that's part of what Earl van Huss is getting after. Kant's Critique of Pure Reason is the "first" phenomenological text. Aristotle's De Anima is the ancient inspiration followed by all the early Greek stuff Heidegger did.

The Adjunct: And so in my own messy and clunky explanations, here's a shot. I too understand myself as a phenomenologist of Geist, and this is how I engaged in ministry. But I quickly came to see that there were and are competing ways of doing theology, and that the doing of theology is not merely an intellectualizing of it, but a lived, first order experience. But all experience has fruitful prejudice that often goes uncritically considered. I would agree that phenomenology is helpfully understood as over against what other option. What is phenomenology responding to or arising from?

The best faith in God can ever hope to achieve and arrive at is a value that each of us holds and that is the determine factor for cultivating the moral life. God collapses into the moral category. Thus, the reason we have people who come to our churches, drop off their kids at confirmation is not to cultivate an imagination for God in the world, although this may (hopefully in the Spirit's lead) happen, it is so that their children can learn morality from the church. Is this a bad thing? Of course, not. But they don't need to be in churches to learn morality. ---Of course, now I'm off the phenomenological track it would seem, but I'm trying to capture the influences that keep people's imagination from a theological phenomena, the givenness of the phenomena where God can be expected, and real.

An example of phenomenology as revealing structure is Ricoeur's sense of the text as explanation-understanding. He identifies a phenomenological "structure" that a reader encounters in textual form. This, of course, has massive implications in terms of how texts are read, but most importantly for doing theology is Scripture in particular. The phenomenological philosophical frame is working to render Kant's categories as impotent and non-reflexive. This sense of the text is massively important for how, then, people engage Scripture, for whom many presume to think that they are to extract principles from the text to apply to their own life. It is rare, in my experience, that the first encounter or consideration of Scripture is the very way God is cultivating a promising relationship with the world. This movement is structurally what Ricouer helpfully "uncovers", is the key word, and that invites a theological interpretive move for what we already confessionally state is the case.

Why phenomenology for theology? It is for the sake of maintaining the category of Truth. Christianity too frequently gives up on Truth, both as a way for framing its own identity, but as well then giving up the market share of Truth to others who offer alternative options. Truth is a significant piece here that most have given up on and collapse into the bi-furcated facts/values split. Now this is Kant, because anything theological has been included as a value, placed within the noumenal field, outside of the observable phenomena.

Phenomenology, the way I am coming to understand it, offers up observable frameworks or structures that appear to be case from the lived experiences, interactions of people and things. These structures, however, are never identified without an interpretive bias that makes claims about what they are; This is where I hear the Professors's piece that phenomenology and hermeneutics are closely aligned.

Also, clearly there are different ways of approaching the subject, as you are seeing on your other phenom-graph networks. one can approach it in terms of practical instances whereby one's posture becomes like a curious child or by attending to its deeper meta-theoretical reasoning, what this philosophical construct assumes as what counts as rationality, truthfulness, and validity over against other options. I'm guessing your more interested in the latter than the former, even as the former comes more naturally, and you like to generate "conversation" with others. Framing the lived four layers of complexity: This has helped me to understand the multiple layers simultaneously operating and how they relate. I'm guessing this isn't new to you, but at least I'm getting it on the table as my working assumption with respect to the possible place of phenomenology. 1. Practical Instances: A situation that arises from lived experience 2. Common Sense: available, "common sense", choices within the situation 3. Theoretical: explanatory frameworks for the lived experience 4 . Meta-theoretical: the underlying assumptions supporting the various explanatory frameworks.

The Cleric: I almost feel like I have some kind of mental "block" on this. I consider myself a pretty smart person, but the whole thing isn't working for me somehow, other than the Professors's first point about fusion of horizons and distantiation. After that I got lost.

The Professor: I'm not sure where the block is -- unless you just have trouble in general with epistemology and hermeneutics.

I just read the whole Oxford Encyclopedia entry on phenomenology. While I have quibbles with it, it's a solid and hefty summary. What are the problems you experience in getting this article?

The Cleric: The block is in what I was signaling from the very beginning. Phenomenology appears to me to be a distinction without a distinction. And I don't mean by this common sense.

Phenomenology asks us (in its Husserlian mode) to bracket what something is according to our natural attitude, how things appear to our senses in order to allow us to consider the object in its full giveness." So, not to add an even fancier word into the mix, but are you and is Husserl saying that the phenomenon is ontological through and through, it discloses being itself?

Because if that is what you are saying, then I agree with it, but I think that's common sense. Most people don't make a distinction between what something is and how they experience it. What it is in its givenness is what it is.

The Professor: Kant's Corpernican turn to the subject means that we are not passive in our knowing things. We don't know things as they are since we actively assimilate the to our categories of understanding. The mind is active in changing forming our experiences. This challenges the basic assumption that many assume that wysiwyg. Or perception is reality. Ph enomenology of Geist is about this basic problem. As far as theology goes, God cannot be an object of our perception in any sense, which is why either Kant's corpernican turn or a basic form of empricisim shows how theological claims are nonsense.

The Adjunct: Very helpful Professor, thanks. Last week a woman in my class told me she's struggling with her faith because she is a psychic. She explained she's had the gift for as long as she can remember, that she communicates with the dead and can relay messages to their living counterparts. At a meal, she said she saw the husband who had died of cancer standing over her widow who was eating dinner right next to her. So she was looking for conversation around how to reconcile it with her faith. We talked for a while about the enchanted ancient world, and then I had her read out loud I Cor. 12 and asked her if anything connected with her. She said she confesses Jesus Lord, and we affirmed this as a gift of the Spirit. Then she read further and identified with the "utterance of knowledge" saying that she has knowledge about people, but doesn't know where it comes from. Very fascinating, so this week she comes back. I'm not nearly as freaked by this as I may have been in the past, particularly around the notion of spirits. This week she was wondering about whether dead people remain on earth for a while or go to heaven, immediately. But that, for another time.

The Cleric: So phenomenology is about this basic problem, that's clear to me. What I don't get is its proposed solution to this problem.

The Professor: The Husserl-Heidegger-Michel Henry-Marion line of phenomenology is about the basic possibility of phenomena -- what makes something a phenomenon, appear. The Merleau-Ponty-Sartre-Levinas-Derrida line is also about that but focuses more on the ethical dimensions of phenomena. Gadamer-Ricoeur is more about phenomenology = hermeneutics . And, there's the kids. I must go. My basic intuition (ha!) here is that you're not going to get this stuff unless you work through Cartesian Meditations or the Idea of Phenomenology. Or even better, I suppose, Marion's how phenomenology saves theology.

The Adjunct: So what the basic problem reconsiders as the conditions for the possibility of knowing is an enchanted world, where the subject is not privileged as the constituting, determinative "ground" of all things? And that this re-introduction of enchantment offers and opens up the possibility once again of God/theology, God's agency/patiency, whatever you choose.

The Professor: Husserl's solution: 1) the principle of all principles: everything that gives itself in intuition must be received as it gives it self i.e. appears. Comment: this is the charge for how phenomenology of Geist works, the imperative that guides it. Ph. has to find a way to make this work, for one to understand/perceive the phenomena as it gives itself. Kant and others step in the way here (even Freud, claiming our knowing is a disaster; even Marx, claiming ideology gives us a false consciousness... depends upon the phenomenologist -- Ricoeur is probably the only one who has taken up all of these obstacles along with Derrida) This is what ties together ph. as a discipline even though there is waay more to even this principle. It is fully articulated in Husserl's complex Ideas, vol. 1. 2) Now we arrive at the debate on how to get at this. Every ph. agrees that the epoche or bracketing is the way to arrive at an understanding of the phenomenon. This is required since natural perception (our unreflective approach to the world) does not allow us to see things as they are. Bracketing is necessary since the stuff that gets in the way (here I am doing violence to Husserl and Heidegger and where a slower read of their work would help) distorts phenomena and therefore our understanding. Bracketing is an act of the subject to eliminate or close out what is and what appears. Thus, Husserl reduces all phenomena to object-hood --- he follows Kant very closely here. This means God cannot be a phenomenon. Heidegger argues with this choice of how to reduce phenomena in Being and Time and prefers possibility -- things that might be, opening up what can count as phenomena to a much wider field. Ricoeur and others follow Heidegger's basic insight. Merleau-Ponty tries to stick to Husserl even though he pushes it to the limits in his posthumous notes.

What do you think of that drastic and horrific summary, Adjunct?

The Adjunct: You are a god. This is an honorable essay, your precision for the details of the argument is massively helpful, clear, and comprehensible. What this tells me is how much ph is a sophisticated argument against Kant's privileging of the subject. This probably why it is good to begin a ph seminar by reading Kant, some of which students may understand, or not, at the first reading. I would also say that Gadamer's Truth & Method is a critique of Kant in the opposite direction, beginning w aesthetics/judgments, then to historically effected consciousness, finally to language itself. While G is hermeneutical emphasis for sure, it's re-worked challenging Kant. It relates to ph in that all ph is fusing of horizons w/in a constantly belonging (given perhaps is what Marion says) structure. Thank you for your words here.

The Cleric: You guys have been very helpful. I now know that my major "block" is with this first and most important point of Husserl's: "the principle of all principles: everything that gives itself in intuition must be received as it gives it self i.e. appears." My problem is I think that might be impossible, in the way it is impossible to "just read the bible."

--

At this point my time allotment for the phenom-graph transcription device had ended, and a line had formed for other users, other purposes. I'm still puzzling over this clearly esoteric yet fascinating discussion. Clearly there are others out there hard at work deciphering aspects of the phenomenology of Geist. []

I sat down at a table alone, near a table with three active graphs. The proprietor kindly allowed me to experiment with a phenom-graph transcription device. I had the opportunity to overhear the following conversation, which I transcribed feverishly. Since I do not know the names of those speaking, I have given them monikers.

--

The Professor: I guess I do not see what is at stake in saying "this phenom-graph is not instrumental" -- when I see people using it as a tool all the time.

The cleric: For me what is at stake is that it doesn't HAVE to be instrumentalized, whereas almost all of the conversation around this assumes it is mostly or even exclusively an instrument. And when it is understood in new non-instrumentalist ways, it furthers mission. That's my stake.

The Professor: To be clear I posed the question: given the positive and mutual beneficient experience you have in mind -- is that experience using Geist media as an instrument or to open up a world/environment? Some have said it is a false dichotomy and waved their hands at habitus, ala Bourdieu. I do not know if this works.

The cleric: I've never linked habitus in my mind with Bourdieu, but then I've probably just not read enough of him. I see opportunities for social media to open up a world/environment. That's why I defend it against implicit or explicit instrumentalization.

The Professor: habitus is supposed to get us over the idea that there's a self and then there's the stuff the self does and that the self is always first. Habitus is to say that the self is in acting. It's in his essay on practice s, he basically said there's no difference than instrument and environment making. I think that skirts a ton of issues because it is basically an attempt to self-hood is fluid and is in practice, which still maintains the priority of the agent . Selfhood is never like that and it is not proper to theological anthropology , selfhood is always ecstatic -- I am who I am in Christ-Geist and in the neighbor-- I am given by another, promised even.

The Adjunct: The phenomenological evidence: When I returned from our conference this afternoon I was greeted by my son's play date he organized on phenom-media...all on their individual devices, proximate or expansive empathy/intimacy? It seems they're cultivating experiences in a shared environment.

The Professor: What is this giving them? that's the other way to think it. Or to put it in terms of hydrogen weapons. It is a tool. But a tool that could utterly change the world. The Eucharist may seem like a tool. But it changes the entire world and selves with it.

The Cleric: There's no difference between an instrumental and environmental use of tech. Mostly people simply aren't even aware of media effects, and this causes all kinds of confusion.

[here there is a mumbled conversation about graphic art I missed while my barrista came to the table offering another espresso]

The Cleric: Hmmmm... I still have no idea what phenomenology is, so I'm probably one without knowing it. And it's not for lack of trying. I've read some of the works by Earl van Huss. Here, take this for example [at which point he read from a book... but one problem with this medium is unless people verbally name their bibliographic reference, there is no way to know]:

Phenomenology is the study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view. The central structure of an experience is its intentionality, its being directed toward something, as it is an experience of or about some object. An experience is directed toward an object by virtue of its content or meaning (which represents the object) together with appropriate enabling conditions.

The Cleric: To me, that's just life. I don't get how it is a philosophical orientation.

The Professor: You would be the first to claim that phenomenology is common sense. I think you're missing the epoche -- the bracketing out of other considerations. To open up the phenomenon.

The Adjunct: For what its worth, my colleague wrote briefly on this topic, asking the question: How does one render public and explicit a supposedly authoritative text in a culture of pluralism in such a way that it functions normatively for real persons? This I believe is a fundamentally phenomenological question.

The Cleric: Okay, you both are helping. This becomes SO frustrating for me. I don't get it. I've tried multiple times to understand how the phenomenology of Geist is a philosophical discipline, and I fail. My only theory right now is that I'm a "natural" phenomenologist and so I don't get the theory around it because it's how I function naturally all the time anyway. What I especially don't get is what you emphasize above, Professor, the "bracketing out of other considerations." What other considerations? This isn't clear to me at all. Here's a quote from the essay you reference, Adjunct, that is an example of why this whole thing remains opaque to me, I guess opaque precisely in its transparency:

"In a quiet and powerful way, it came to me that phenomenology precisely offered the practices that assisted my faithful dwelling in God’s Word and world. Phenomenology gave me the practices of attentiveness, wakefulness, critical but generous attending to the given that all the prejudices, both fruitful and unfruitful, framed, shaped, ordered, and dominated my reading of Word and world. Phenomenology was the helpful discipline that made possible a liberation from drowsy acceptance and acquiescence to Word and world. My use of phenomenology became more intentional. The practices of bracketing, folding, critical distance, and seeking a critical participation in the fusing horizons of Word and world became increasingly powerful, fruitful for seeking truth regarding my persistent question."The Cleric: Here's another quote... isn't this obviously how everyone should read the bible? "Ricoeur’s three fold hermeneutics of (1) good will, (2) critical suspicion, and (3) doubt of self remains my working meta-hermeneutics."

The Professor: Here's probably why you are having trouble: 1) phenomenology and hermeneutics dovetail into each other with Gadamer -- you've probably drunk so deeply here that some of the habits of thought that constittue how you look at things or read texts is phenomenological. This includes: 1) the idea of horizons and its fusion 2) the language of the "other" and distanciation .

Theology of the cross does not say things are what they seem to be. Phenomenology asks us (in its Earl van Hussian mode) to bracket what something is according to our natural attitude, how things appear to our senses in order to allow us to consider the object in its full giveness. Things are, according to van Huss, what they are according to how they give themselves. For Heidegger, things disclose being -- this is why for Heidegger technology is so important becuase tech changes the way we are, our very being, our very world. Things are, according to Marion, their giveness. Phenomenology is not just to attend to our senses but to consider how things are while our natural attitude is left aside. This allows us to consider what truth is disclosed in fiction in the phenomenological sense.

Theology of the cross is a quasi-phenomenological exercise since it asks us to bracket out our desire to write God large and see how suffering discloses God. you are not considering the problems that Kant introduced to which phenomenology is in large part the answer. Kant's distinction between phenomena and noumena. Our knowing can never get to what things are in themselves, according to Kant, to drastically simplify.

Being Given by Marion is your ticket. Or Husserl's Cartesian Meditations. I don't know any other way here. Read it and tell me what doesn't work. If you don't get the Kant problems on knowing and how one can't have an experience of God in his critique of what he calls the transcendental ideas (God, human self/soul, and human freedom) that's part of what Earl van Huss is getting after. Kant's Critique of Pure Reason is the "first" phenomenological text. Aristotle's De Anima is the ancient inspiration followed by all the early Greek stuff Heidegger did.

The Adjunct: And so in my own messy and clunky explanations, here's a shot. I too understand myself as a phenomenologist of Geist, and this is how I engaged in ministry. But I quickly came to see that there were and are competing ways of doing theology, and that the doing of theology is not merely an intellectualizing of it, but a lived, first order experience. But all experience has fruitful prejudice that often goes uncritically considered. I would agree that phenomenology is helpfully understood as over against what other option. What is phenomenology responding to or arising from?

The best faith in God can ever hope to achieve and arrive at is a value that each of us holds and that is the determine factor for cultivating the moral life. God collapses into the moral category. Thus, the reason we have people who come to our churches, drop off their kids at confirmation is not to cultivate an imagination for God in the world, although this may (hopefully in the Spirit's lead) happen, it is so that their children can learn morality from the church. Is this a bad thing? Of course, not. But they don't need to be in churches to learn morality. ---Of course, now I'm off the phenomenological track it would seem, but I'm trying to capture the influences that keep people's imagination from a theological phenomena, the givenness of the phenomena where God can be expected, and real.

An example of phenomenology as revealing structure is Ricoeur's sense of the text as explanation-understanding. He identifies a phenomenological "structure" that a reader encounters in textual form. This, of course, has massive implications in terms of how texts are read, but most importantly for doing theology is Scripture in particular. The phenomenological philosophical frame is working to render Kant's categories as impotent and non-reflexive. This sense of the text is massively important for how, then, people engage Scripture, for whom many presume to think that they are to extract principles from the text to apply to their own life. It is rare, in my experience, that the first encounter or consideration of Scripture is the very way God is cultivating a promising relationship with the world. This movement is structurally what Ricouer helpfully "uncovers", is the key word, and that invites a theological interpretive move for what we already confessionally state is the case.

Why phenomenology for theology? It is for the sake of maintaining the category of Truth. Christianity too frequently gives up on Truth, both as a way for framing its own identity, but as well then giving up the market share of Truth to others who offer alternative options. Truth is a significant piece here that most have given up on and collapse into the bi-furcated facts/values split. Now this is Kant, because anything theological has been included as a value, placed within the noumenal field, outside of the observable phenomena.

Phenomenology, the way I am coming to understand it, offers up observable frameworks or structures that appear to be case from the lived experiences, interactions of people and things. These structures, however, are never identified without an interpretive bias that makes claims about what they are; This is where I hear the Professors's piece that phenomenology and hermeneutics are closely aligned.

Also, clearly there are different ways of approaching the subject, as you are seeing on your other phenom-graph networks. one can approach it in terms of practical instances whereby one's posture becomes like a curious child or by attending to its deeper meta-theoretical reasoning, what this philosophical construct assumes as what counts as rationality, truthfulness, and validity over against other options. I'm guessing your more interested in the latter than the former, even as the former comes more naturally, and you like to generate "conversation" with others. Framing the lived four layers of complexity: This has helped me to understand the multiple layers simultaneously operating and how they relate. I'm guessing this isn't new to you, but at least I'm getting it on the table as my working assumption with respect to the possible place of phenomenology. 1. Practical Instances: A situation that arises from lived experience 2. Common Sense: available, "common sense", choices within the situation 3. Theoretical: explanatory frameworks for the lived experience 4 . Meta-theoretical: the underlying assumptions supporting the various explanatory frameworks.

The Cleric: I almost feel like I have some kind of mental "block" on this. I consider myself a pretty smart person, but the whole thing isn't working for me somehow, other than the Professors's first point about fusion of horizons and distantiation. After that I got lost.

The Professor: I'm not sure where the block is -- unless you just have trouble in general with epistemology and hermeneutics.

I just read the whole Oxford Encyclopedia entry on phenomenology. While I have quibbles with it, it's a solid and hefty summary. What are the problems you experience in getting this article?

The Cleric: The block is in what I was signaling from the very beginning. Phenomenology appears to me to be a distinction without a distinction. And I don't mean by this common sense.

Phenomenology asks us (in its Husserlian mode) to bracket what something is according to our natural attitude, how things appear to our senses in order to allow us to consider the object in its full giveness." So, not to add an even fancier word into the mix, but are you and is Husserl saying that the phenomenon is ontological through and through, it discloses being itself?

Because if that is what you are saying, then I agree with it, but I think that's common sense. Most people don't make a distinction between what something is and how they experience it. What it is in its givenness is what it is.

The Professor: Kant's Corpernican turn to the subject means that we are not passive in our knowing things. We don't know things as they are since we actively assimilate the to our categories of understanding. The mind is active in changing forming our experiences. This challenges the basic assumption that many assume that wysiwyg. Or perception is reality. Ph enomenology of Geist is about this basic problem. As far as theology goes, God cannot be an object of our perception in any sense, which is why either Kant's corpernican turn or a basic form of empricisim shows how theological claims are nonsense.

The Adjunct: Very helpful Professor, thanks. Last week a woman in my class told me she's struggling with her faith because she is a psychic. She explained she's had the gift for as long as she can remember, that she communicates with the dead and can relay messages to their living counterparts. At a meal, she said she saw the husband who had died of cancer standing over her widow who was eating dinner right next to her. So she was looking for conversation around how to reconcile it with her faith. We talked for a while about the enchanted ancient world, and then I had her read out loud I Cor. 12 and asked her if anything connected with her. She said she confesses Jesus Lord, and we affirmed this as a gift of the Spirit. Then she read further and identified with the "utterance of knowledge" saying that she has knowledge about people, but doesn't know where it comes from. Very fascinating, so this week she comes back. I'm not nearly as freaked by this as I may have been in the past, particularly around the notion of spirits. This week she was wondering about whether dead people remain on earth for a while or go to heaven, immediately. But that, for another time.

The Cleric: So phenomenology is about this basic problem, that's clear to me. What I don't get is its proposed solution to this problem.

The Professor: The Husserl-Heidegger-Michel Henry-Marion line of phenomenology is about the basic possibility of phenomena -- what makes something a phenomenon, appear. The Merleau-Ponty-Sartre-Levinas-Derrida line is also about that but focuses more on the ethical dimensions of phenomena. Gadamer-Ricoeur is more about phenomenology = hermeneutics . And, there's the kids. I must go. My basic intuition (ha!) here is that you're not going to get this stuff unless you work through Cartesian Meditations or the Idea of Phenomenology. Or even better, I suppose, Marion's how phenomenology saves theology.

The Adjunct: So what the basic problem reconsiders as the conditions for the possibility of knowing is an enchanted world, where the subject is not privileged as the constituting, determinative "ground" of all things? And that this re-introduction of enchantment offers and opens up the possibility once again of God/theology, God's agency/patiency, whatever you choose.

The Professor: Husserl's solution: 1) the principle of all principles: everything that gives itself in intuition must be received as it gives it self i.e. appears. Comment: this is the charge for how phenomenology of Geist works, the imperative that guides it. Ph. has to find a way to make this work, for one to understand/perceive the phenomena as it gives itself. Kant and others step in the way here (even Freud, claiming our knowing is a disaster; even Marx, claiming ideology gives us a false consciousness... depends upon the phenomenologist -- Ricoeur is probably the only one who has taken up all of these obstacles along with Derrida) This is what ties together ph. as a discipline even though there is waay more to even this principle. It is fully articulated in Husserl's complex Ideas, vol. 1. 2) Now we arrive at the debate on how to get at this. Every ph. agrees that the epoche or bracketing is the way to arrive at an understanding of the phenomenon. This is required since natural perception (our unreflective approach to the world) does not allow us to see things as they are. Bracketing is necessary since the stuff that gets in the way (here I am doing violence to Husserl and Heidegger and where a slower read of their work would help) distorts phenomena and therefore our understanding. Bracketing is an act of the subject to eliminate or close out what is and what appears. Thus, Husserl reduces all phenomena to object-hood --- he follows Kant very closely here. This means God cannot be a phenomenon. Heidegger argues with this choice of how to reduce phenomena in Being and Time and prefers possibility -- things that might be, opening up what can count as phenomena to a much wider field. Ricoeur and others follow Heidegger's basic insight. Merleau-Ponty tries to stick to Husserl even though he pushes it to the limits in his posthumous notes.

What do you think of that drastic and horrific summary, Adjunct?

The Adjunct: You are a god. This is an honorable essay, your precision for the details of the argument is massively helpful, clear, and comprehensible. What this tells me is how much ph is a sophisticated argument against Kant's privileging of the subject. This probably why it is good to begin a ph seminar by reading Kant, some of which students may understand, or not, at the first reading. I would also say that Gadamer's Truth & Method is a critique of Kant in the opposite direction, beginning w aesthetics/judgments, then to historically effected consciousness, finally to language itself. While G is hermeneutical emphasis for sure, it's re-worked challenging Kant. It relates to ph in that all ph is fusing of horizons w/in a constantly belonging (given perhaps is what Marion says) structure. Thank you for your words here.

The Cleric: You guys have been very helpful. I now know that my major "block" is with this first and most important point of Husserl's: "the principle of all principles: everything that gives itself in intuition must be received as it gives it self i.e. appears." My problem is I think that might be impossible, in the way it is impossible to "just read the bible."

--

At this point my time allotment for the phenom-graph transcription device had ended, and a line had formed for other users, other purposes. I'm still puzzling over this clearly esoteric yet fascinating discussion. Clearly there are others out there hard at work deciphering aspects of the phenomenology of Geist. []

Monday, November 19, 2012

Thomas Cranmer: Collects for Zombie Advent

-->

'Tis the Season of Advent, and the Zombies are upon Us. Let us pray and fight, to the glory of God.

Blessed

Lord, who has caused all holy Scripture to be written for our Learning; grant

that we may so hear Them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest Them; that by Patience,

Axes, and comfort of thy Holy Word we may embrace and ever hold fast the

blessed Hope of Eternal Life, though not of Zombie eternal unliving, which Thou

hast given us in our Savior, Jesus Christ. Amen.

Almighty

God, who dost make the Minds of all Men to be of one Will; grant unto Thy People,

that they may love the Thing which Thou commandest, and desire that which Thou dost

promise, that among the sundry and manifold Changes of the World, our Hearts

may be surely fixed to put to ruin the Zombie Hoards, through Jesus Christ our

Lord. Amen.

God,

which hast prepared to Them that love Thee such Good Things as pass all man’s Understanding; Pour into our Hearts such Love toward thee, That we loving Thee

in all Things, even Those who have gone to Zombie, may obtain Thy Promises,

which exceed all that we can desire; through Christ our Lord. Amen.

Almighty

and Everlasting God, Who art always more ready to hear than we to pray, and art

wont to give more than either we desire or deserve, pour down upon us the

abundance of thy mercy, forgiving us those things whereof our conscience is

afraid and giving unto us that which our prayer dare not presume to ask,

especially when we must slay our Loved Ones who have been consumed by the

Undead; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Almighty

and everlasting God, give unto us the Increase of Faith, Hope, Strong Limbs for

an Axe, and Charity, that we may obtain That which thou dost promise, make us

to love that which Thou does command; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Monday, October 29, 2012

"And the Dead Shall Rise?": Part II: A Priest Walks into a Bar

28 October 1899

To the Ecclesiast and the Magus,

You will be glad to know that I have discovered I am not mad. But the other side of this claim is that the ghastly vision of Mount Hope Hill was no hallucination or fiction. Shortly after I sent my last correspondence, which in all likelihood has yet to reach your eyes, I found myself inundated by a throng of souls - these ones, very much alive, and quite frightened, from within my flock and without - whose hearts are full of dread and of questions. For they too, it seems, have seen, not just my solider, but others as well.

God be praised, none of the people had had as close a brush with the creatures as had I. Most had glimpsed them, almost by accident, and at quite a distance. Or, had created said distance as quickly as could be afforded. However, they almost unanimously agreed upon a most disturbing crimson thread to this strange affair: all had witnessed the presence of the dead outside of the very church, my church, in which we sat during the daylight hours. And, as if this were not enough to freeze the blood, those who were able to discern visages - on those that had any visage to speak of - recognized them as being, like my solider, past members of the congregation.

What is this, that my person and my parish should be the nexus of this series of unholy resurrections? I must confess, after the first encounter, the thrill of adventure readily distilled theories and ideas from my imagination. But on this day, and at this writing, I am simply overwhelmed. And, in spite of the exhortations of angels, more than just a bit afraid.

Up the street from our church is Dicky’s Public House, where, after an exhausting day of having my ignorance largely on public display, I went avail myself of a lager brewed along the Genesee River to clear my head and still my heart. The patrons there are accustomed to my presence, and after a century of Methodism, seem grateful for the implication of the Lord’s love of beer, and by extension, themselves, as evidenced by His providential creation of Lutherans.

Up the street from our church is Dicky’s Public House, where, after an exhausting day of having my ignorance largely on public display, I went avail myself of a lager brewed along the Genesee River to clear my head and still my heart. The patrons there are accustomed to my presence, and after a century of Methodism, seem grateful for the implication of the Lord’s love of beer, and by extension, themselves, as evidenced by His providential creation of Lutherans. And there, too, the spectre of the past persisted in the rumors and whispers of immigrant Irishmen who seemed as shocked as any rationalist to discover "living" proof of their deepest superstitions. Not wishing to continue on the subject, but wishing less to shirk my priestly office, I listened intently as frightened papists forgot their Catholicism and offered me their confessions of what they had seen.

Apparently, those of the Celtic regions of Britain have long believed, from the misty past before the Empires of the Romans and the Christians transmogrified their faith into instruments of propaganda, that at the very time we remember the feasts of All Souls and All Saints, the barrier between the realm of the living and of the dead is stretched particularly thin. That is to say, this season is a kind of vortex, almost a gateway, in which mingle the realm of spirit and the realm of matter.

You will recognize, perhaps, the origins of the vogueish celebration of Halloween, which has recently taken our towns and villages by storm, at least, here in New England. It was to the stirrings of the ancient creatures of the Old World, in times when the eyes of mens' hearts beheld more and doubted less, a time before even Faerie and mythology, that these men appealed. Not unaided, I might add, by the spirits of this age which they imbibed liberally in their terror and nostalgia. The past is prelude, perhaps - or perhaps, has never really past at all.

Lost in brew-induced reveries of the shadowy times of druid and warrior and pagans baking soul cakes donning costumes of animal skins with which to maintain commerce with things unfit for modern "enlightened" sensibilities, we were startled suddenly when the door of the tavern swung violently open. Every man there leaped up in anticipation of the incarnation of their nightmares, but what they beheld was perhaps far more imposing.

I knew immediately from my travels, and from the goggles that held back her locks, that she was an airship captain. After a penetrating glance around the room so confident that it deigned not even to challenge so sordid a lot as offended her dignity, she strode to the bar took the stool to my right. Noticing my clerical garb, she introduced herself as Captain Cherie Priest, relishing the irony with self-satisfied sarcasm. But she was not haughty. I know the type gentlemen; she was above us, not only because she sailed the skies, but because she was also above that which held us captive. She was free from fear.

I knew immediately from my travels, and from the goggles that held back her locks, that she was an airship captain. After a penetrating glance around the room so confident that it deigned not even to challenge so sordid a lot as offended her dignity, she strode to the bar took the stool to my right. Noticing my clerical garb, she introduced herself as Captain Cherie Priest, relishing the irony with self-satisfied sarcasm. But she was not haughty. I know the type gentlemen; she was above us, not only because she sailed the skies, but because she was also above that which held us captive. She was free from fear. Captain Priest informed me she was newly landed on what she called a trading run (though I knew beyond a doubt hers were darker purposes; a smuggler, most likely) from the port of Seattle, in Washington, far beyond even my beloved mountains in the West. I brought her into our talk of things undead, and at the mention, she became more gravely serious than I thought possible for someone so strong. Evidently, this was no marvel to her.

She was evidently a kind of expert on the creatures, having come run across them in her own dealings, and also claiming the distinction of having written several dispatches and reports for assorted newspapers across the country (some, she told me later, had even been made into three-penny novels, though at present, she was short on copies to lend me).

Apparently, for decades there had been talk of such apparitions - “walkers” she called them - torn from the ranks of both the living and the dead. Some believed they began with benighted ex-soldiers of the great wars of this past century who, driven by despair, began to imbibe a certain opium-like substance known in the back alleys as “Blight.” Some speculated that prolonged abuse of the drug led to a kind of suspended animation of life, of the sort Dante describes of certain souls in Hell whose bodies continue to walk in daylight, while their souls already languish in the darkness.

But, I countered, what of the obviously dead former parishioner in the cemetery? Surely this drug’s effects could not linger for nigh half a century? And could it be merely coincidence that the locus of this paranormal activity, this refusal of the past to remain past, should haunt my parish, my people, in particular?

She told me she was not sure, that she held to the materialist explanation, that she had no time for other peoples' gods, other peoples' superstitions, other peoples' histories. But, she went on, regardless of their origins, you must heed their present danger. She said she would not be surprised if some of the walkers we witnessed were not so long dead. You see, she informed us, if one were to bite, or even scratch one of the fully alive, they would not remain long among the living. To be touched too deeply by the walker is to become a walker oneself.

We remained there long after the Irishmen returned to their homes or left for their evening shifts along the docks of the Erie Canal. I cannot relate all of the things she shared with me, though I subsequently procured one of her novellas, Bonecrusher by name, and if you are able to purchase one yourself, it does much to deepen her theories on the origins of the creatures - not to mention, would, I imagine, provide a great deal of delight were one not seemingly caught in the midst of the reality of its antagonists.

I longed to join Captain Priest and her crew, wherever they were flying off to, to ascend above the yellow fog of this haunted city and reclaim lost freedom. But such is not the vocation which heralds me at present. I will keep you informed as I am able, and if you chance to receive this soon and have discovered anything that may help, do please wire it to me - I will pay you back when we meet again.

And above all, pray for us brothers. And for my people. And, dare I ask, for those who the walkers were once, and may still be, and those who very well might join them, and for God knows what happens to their souls, and to all of ours as well.

Grace and peace, and may God have mercy upon us,

The Alpinist

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

"And the Dead Shall Rise?": Part I - Monstrosity on Mount Hope Hill

24 October 1899

To the Ecclesiast and Magus,

Please forgive the lack of the customary formalities, my friends. But I write to you with utmost haste, longing for the day when our inventors discover the means by which my words might somehow appear to you in the same instance as I write them.

I have not been long at my post here in Rochester, and already, I have the most fantastical tale of the supernatural to report. The rub is, of course, that I am not quite sure, that these are the variety of tellings as would please pious ears. But let me attempt to paint a backdrop for the phantasmagoria to follow.

I have not been long at my post here in Rochester, and already, I have the most fantastical tale of the supernatural to report. The rub is, of course, that I am not quite sure, that these are the variety of tellings as would please pious ears. But let me attempt to paint a backdrop for the phantasmagoria to follow.

Bordering upon the ward of this burgeoning city where the bishop has seen fit to establish an advance missional outpost out of the Lutheran Church of Peace, there is a cemetery. It rests upon Mount Hope Hill, bearing the same name, and in the seventy some years of its existence, has come to boast of architectural beauties in the Gothic, Florentine, and even the Egyptian styles. Our recently departed brother Frederick Douglass, one of my spiritual ancestors here in Rochester, lies awaiting the sound of the trumpet. An exquisite place it is, and often the choice of fellow citizens of the Flour City for strolls following Sunday morning services.

It was just this past Sunday that I found myself on such a stroll with a charming young lady from the outlying village of Penfield. Escaping the clamor of parishioners intent on my romancing their memories of the parish’s glory days of yore rather than said young lady, we ascended to a vantage point known as The Fandango in the hopes of observing what locals call “the Rochester Mirage” - that is, a rare glimpse of the northern shore of Lake Ontario, over 60 miles away, with supposedly staggering clarity. Hardly an effort for an Alpinist, naturally, but a welcome climb all the same. And, of course, as is wont with this gloomy place, the sun was shackled in the grey irons of rain clouds. Dejected, we turned back. And beheld what I hoped, surely, must be yet another mirage. But it was not.

It was just this past Sunday that I found myself on such a stroll with a charming young lady from the outlying village of Penfield. Escaping the clamor of parishioners intent on my romancing their memories of the parish’s glory days of yore rather than said young lady, we ascended to a vantage point known as The Fandango in the hopes of observing what locals call “the Rochester Mirage” - that is, a rare glimpse of the northern shore of Lake Ontario, over 60 miles away, with supposedly staggering clarity. Hardly an effort for an Alpinist, naturally, but a welcome climb all the same. And, of course, as is wont with this gloomy place, the sun was shackled in the grey irons of rain clouds. Dejected, we turned back. And beheld what I hoped, surely, must be yet another mirage. But it was not. As if in some perverse aping of the very promise we are to celebrate on the first of November, this was a resuscitated body. But let me be clear, it was only a body, for there was no evidence or glow of soul within the hollowed rotten eyes that greedily locked upon mine. I grabbed my lady’s hand and as quickly as possible, I turned and fled, fearing her safety. The poor devil was not much of a sprinter, and soon the infernal strains of its gasping and wheezing trailed off like a nightmare dissolving in the dawn.

As if in some perverse aping of the very promise we are to celebrate on the first of November, this was a resuscitated body. But let me be clear, it was only a body, for there was no evidence or glow of soul within the hollowed rotten eyes that greedily locked upon mine. I grabbed my lady’s hand and as quickly as possible, I turned and fled, fearing her safety. The poor devil was not much of a sprinter, and soon the infernal strains of its gasping and wheezing trailed off like a nightmare dissolving in the dawn.

I dared not speak of this strange encounter with any of my fellow clergymen, and as she borded the air-cab home, urged my traumatized lady to remain silent on the matter until I could consult with you both. I have not seen that soldier again. But believe me when I tell you, friends: this was no coincidence. For not wishing to be known as a coward, I returned to Mount Hope to investigate the grave stones of veterans, and, I swear by the cross, I found one empty tomb among their ranks. And would you not believe it, the very one belonged to the grandfather of one of the youth in my parish - of this I am certain, for I asked this young man to tell me again his old family stories, and verified the name.

Now, it is well known that communities facing change have a tendency to cling to an idealized past. And churches are certainly no exception to the rule. But the past clinging to us, the past refusing to remain the past, clawing itself out of the very grave when we thought it rested until the Day of Judgement - as if to turn its undead eye of condemnation upon the efforts of our present, casting its long shadow across the the bright if uncertain horizons of the future?

Undoubtedly, naturalistic and materialist solutions will be proposed. Perhaps the Ecclesiast will imagine this to be one of his steam-induced visions, though in all fairness, a good pipe and cask of ale suit me better, and neither is known to bend one towards hallucination. Nor does it account for corroboration of the youth. All Souls, All Saints, and of course, that mischievous festival of All Hallows Eve, loom on the horizon. In but a few months, this wondrous, chaotic century will wind down like a doomsday clock, unleashing God knows what marvels and what horrors as a new era dawns.

And so, brothers, I turn to you for advice. What do you make of this phenomenon? Could it be the work of the Evil One, long consigned to the strategic obscurity of mythology and skepticism, stirring up the Powers that Be to combat the work of the Gospel, as our dear Dr. Luther warned would happen on the eve of his own revolution, which we also celebrate in the coming week? What is the connection between the victim of warfare, the buried, persistent history of my parish, and the present age? What should I do?

This much is certain: the rising of the dead is for me no longer a question of speculation, theory or theology; it is a mystery bordering on monstrosity. Like a second Horatio, this horror confronts me like a maddened Hamlet, warning me that "there are more things in heaven and earth...then are dreamt of in your philosophy."

I am used to ascending the heights - I knew my return home would mean a descent. But a descent into the valley of the shadow of death? The irony, of course, is that the hill of my recent climb bears the name of Hope. The very thing my hero Dante was commanded to abandon by the gates of Hell.

I am used to ascending the heights - I knew my return home would mean a descent. But a descent into the valley of the shadow of death? The irony, of course, is that the hill of my recent climb bears the name of Hope. The very thing my hero Dante was commanded to abandon by the gates of Hell.

Thank you good sirs. Pray for us in a manner you see fit. And may God have mercy on us all,

The Alpinist

Saturday, October 20, 2012

Steamwalking

Dear Magus (and if he sends it on, Alpinist),

I have for the past few weeks been unimaginably ill. I wish I could exchange my lungs for new ones. A few nights I have filled my reading room with steam, and falling asleep, experienced a liminal space of incredible richness. I had no idea, honestly, that darkness, combined with steam, combined with the tired haze of feverish mind, could simulate the instability of passage over ley lines.

One night in particular, having just finished reading a particularly fine essay in temporal philosophy, I fell asleep. Or thought I did. The next moment, I was in a reading at a library.

But a library that had no books. Well, each attendee had one book, their own. I was alone in my poverty, no book in hand. I asked to borrow a book from the gentlemen next to me, only to be re-buffed, strongly.

"That simply is not done! Who are you, sir? Where are you from?"

I quickly begged off, pointing out my ill health, but need for intellectual stimulation in spite of my fever. My neighbor seemed mollified, but gave me a few more looks. Then the reading began.

Imagine, that you could only experience a book by going to a reading, or by reading the text off a screen that displayed it only briefly before disappearing. This is what is what I experienced that night. Each reader came forward and read their work to us. Then they sat down, their book firmly in hand. If I wished to retain what they had read, it was completely dependent on my memory. I did not even have a notebook.

Imagine, that you could only experience a book by going to a reading, or by reading the text off a screen that displayed it only briefly before disappearing. This is what is what I experienced that night. Each reader came forward and read their work to us. Then they sat down, their book firmly in hand. If I wished to retain what they had read, it was completely dependent on my memory. I did not even have a notebook.

I understand that this reading was also simultaneously broadcast via some strange device to several libraries around the city. Readers in these libraries drew close to the screens, attempting to discern the expression of each reader and vocal inflection as they read.

It was then that I awoke (or traveled) back to my steamy library. I still am not quite sure. What I know for certain is that my entire theological sense of the presence of Christ as the living Word was shaken, to the core. Christ is not in this or that or any book, not even the individual books we keep in our little churches. He is ever and always only spoken. Let us be attentive. This was my theological awakening.